Beyond Modernism with Peter Newman: Transforming Cities to Coexist with Nature

Environmentalist, author and educator Peter Newman led a campaign to save the railway in Perth in 1979—and won. Photo: Supplied.

This is part one of an interview with Peter Newman. Part two—coming soon—dives into Biophilic Urbanism and Indigenous Landscaping. Subscribe so you don’t miss it.

From pioneering environmental science to championing biophilic design and regenerative urbanism, Professor Peter Newman has devoted his life to reimagining how humans coexist with nature in cities. An environmental scientist, author and educator, Newman is a Professor of Sustainability at Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia. He has built a distinguished body of work by challenging modern urbanism and calling the “wild” into how we build, live and relate to our surroundings.

In conversation with The Biophilic Blueprint, Newman reflected on three phases of his career—each marking a shift not only in his own work, but in the broader environmental conversation as it has evolved over time. We explored the passion that drives his focus on sustainability and biophilia, alongside his critique of modernism in the built environment.

“A lot of my writing's been about challenging modernism,” he says. “We do not want to continue to have a town planning scheme that essentially rolls out modernism, and we continue to do it, but it's not leading to the kind of city we need.”

“I'm an action person, and that is very much part of my spirituality. I see action as my way of providing hope and then writing stories about how it works,” he adds. “You have to show that there is a better way and that it is something that involves nature. You cannot deny it,” Newman said about the importance of a continual “attitude change” in how we design and live within cities. For him, the built environment must do more than minimise harm—it must actively welcome nature back in.

Newman was a pioneer of one of the world’s first environmental science programs, 50 years ago this year. “I was given a job at Murdoch University to help start environmental science, being one of the few people in the world that had studied this. We were the first university to do environmental science,” he said. Newman’s environmental journey started with a PhD in chemistry at the University of Western Australia, though he quickly realised it wasn’t his path. “My early days, I knew I would never be a chemist for very long, but never quite knew where it would go. I went to the very first Earth Day event in 1970, and that was where I realised that environmental matters were going to draw me into my life's work,” Newman recalls.

“I began to see that I needed to shift my direction towards doing something where I could contribute to planetary ecological matters, and have been there ever since.”

However, for Newman his journey began long before his career. He was born in Perth but relocated to the Dandenong Ranges in Victoria as a child. “I was a really wild child, because my dad was in the Air Force away most of the time. Us kids, and there were five of us, we just took off into the bush around and mum didn't mind, as long as we got back for dinner. That kind of life is very hard to get these days, but we had a very nature-oriented childhood,” Newman told The Biophilic Blueprint.

Even after moving back to Perth city, the wildness of those early years never left him. It would become a central influence on his lifelong work in sustainability and urban design.

The Professor’s work has long been defined by this willingness to challenge entrenched ways of thinking—most notably, the modernist approach to urban planning. “Modernism was invented in the 20s and 30s, with Le Corbusier’s team in Europe,” Newman explains. “They had this voyage through the Greek islands and formed the Modernist Principles, which were essentially about knocking down the old world which they said had lost its way—and creating a new kind of city built around the car, which was seen as a freeing device.”

He explained that modernist principles promoted “high rise buildings” and city designs that removed walkability and any connection to nature. “The modernist view of planning and design is still pretty much what is taught, and still very much part of the system,” Newman tells The Biophilic Blueprint.

Peter Newman with wife Jan Newman at home in Perth. Photo: Supplied.

For Newman, challenging modernist principles remains a central focus, as he embraces concepts such as biophilic design and Indigenous landscaping to cultivate regenerative urbanism. A recent paper co-written with Agata Cabanek and Noel Nannup called Indigenous Landscaping and Biophilic Urbanism: Case Studies in Noongar Six Seasons, delves into the future of biophilic urbanism.

Never losing touch with the wild Side

Beyond his professional achievements, Newman’s personal journey illustrates why understanding our environment is critical for everyone. Too often, a lack of connection to nature leads to poor decisions about how we build and inhabit cities. In contrast, Newman has drawn on his curiosity and early experiences in the bush to go deeper, listening to the landscape itself and allowing it to guide his research into biophilic and regenerative urbanism.

But it wasn’t easy for Newman. Returning to Perth, he reflected on how WA’s unique landscapes were very different from those of his youth, requiring him to get out, explore, and challenge his own assumptions.

“This (Western Australia’s landscapes) is not the same as the bush I grew up in,” Newman explains. Reflecting on the work of environmental thinker George Seddon, and his book Sense of Place, he says: “He came back to Australia from Canada as a lecturer in English at UWA and went into the bush and said he hated it. He couldn't believe this was seen as bush. And he realised then, that he was not an Australian, he was a Victorian, as was I, and that in reality, we have to come to terms with that.”

Photo 1952: Peter Newman in Grade 2 at Upwey Primary School in the Dandenong’s—fifth from the right at the back. Photo 1947: Peter Newman, 2, held by his father. His grandfather, in the middle, set up the blackboy industry that blew up.

The writings of Seddon provided a vital guide to understanding the unique character of WA’s landscapes. “His book was very important for me to understand that transition and to come to terms with it,” Newman reflects. “Having that kind of understanding is something you have to experience as well as read about.”

Newman also recalls reading his grandfather’s writings from the 1930s, which helped him understand Western Australia’s history and its relationship with the bushland during that era. “I discovered my grandfather, on my father's side, had a business in the 1930s which was processing black boys, as they were called, and balgas now,” he said.

The Noongar word for the native grass tree is balga (bal-gah) while its scientific name is Xanthorrhoea preissii—a widespread species found across WA’s South West.

“These were found to have all kinds of special chemicals, and they were processing them in a big factory in East Perth and exporting them to Germany before the war. That process would have stripped our bush of balgas because they are very slow growing.” The industry came to an abrupt halt when the factory exploded—an accident that spared the region’s balga population. “Fortunately, the industrial plant blew up because the person who was meant to undo the pressure valve got drunk—and it saved our bush,” he said.

Studying local landscapes over time showed Newman that reimagining cities to integrate nature requires understanding places and their differences—a lesson he would carry throughout his career. “Walking, seeing and feeling that bush—and truly understanding it,” Newman says has been vital to challenging modernist thinking in the built environment.”

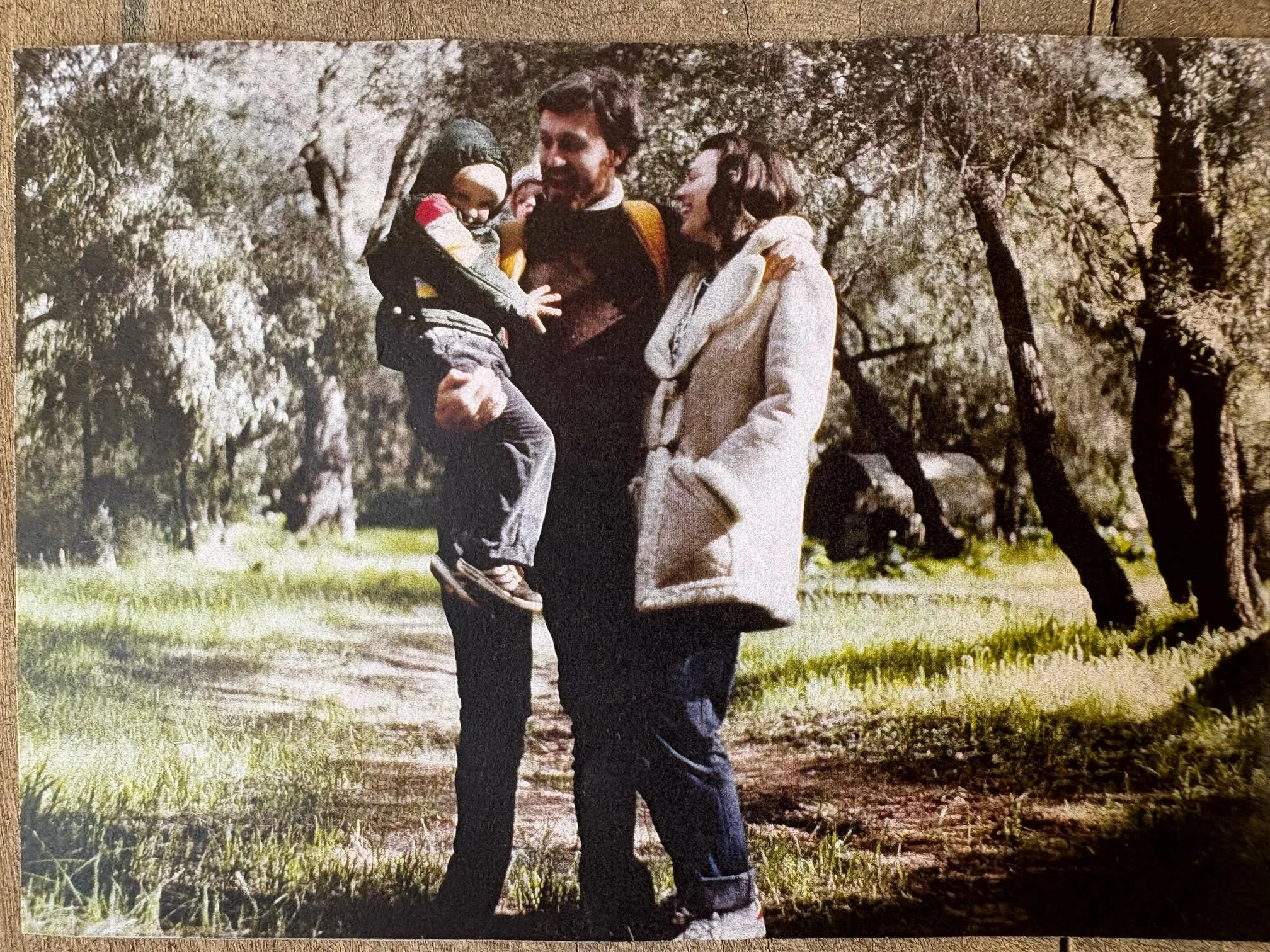

Peter with wife Jan and first child Christy on a bush walk in 1978.

The journey through cities and change

After establishing a foundation in environmental science, Newman’s focus broadened to sustainability—recognising that ecological concerns could not be addressed solely through science and technology. “I spent my first phase of my career, if you like, setting up environmental science, and I got onto the EPA and started a career of public advocacy and work, and got on the Fremantle City Council and was doing all kinds of things there.

“That then journeyed into sustainability, because we realised after a while that environmental science as a Science and Technology emphasis needed to get into the structures of society much more,” he explained. “Seeing how environmental issues needed to be dealt with in the economy and society and culture of the world was something that I really gravitated to.”

This realisation led Newman to explore the humanities. “I started the Institute for Sustainability and Technology Policy at Murdoch, and worked that in that area, which is where I came across Tim Beatley,” he said. The institute became a hub of global sustainability research, boasting over 100 PhD students and pioneering work in sustainability policy. “We were the biggest sustainability policy institute in the world at that time,” Newman recalls.

Newman’s work continued at Curtin University, where Newman found a fertile environment to advance his sustainability research. It was during this period that he encountered Tim Beatley, the urban planner widely regarded as a pioneer of biophilic urbanism.

“Tim Beatley came and worked with us. Tim Beatley is the person who wrote most of the first books about biophilic urbanism—and a terrific friend of mine. He still runs the Biophilic Cities Network around the world, and so I got very much into that as part of the sustainability policy arena.

“We shared the ability to write about that and bring people together so that we could do research that was based on telling their stories. And that's what we do together, telling the stories of hope, because in this transition, you cannot just scare people into the future,” Newman explains.

Newman’s career has extended to the international stage. “I got asked to join IPCC, and for the last 15 years, I've been very much working with them on what it all means to help with climate change issues, and that change I have now written about in my 26th book, which is called Net Zero Cities with Sustainability—A Practitioner’s Approach.”

“It's cities oriented, which has been my focus. That includes all of the biophilic work. It includes all of the work on transport that I've done. And it is something that brings to light the amazing journey that I've been on, but which the world has been on as well, because we are now much more committed to these matters," Newman says.

“It’s still an enormous struggle, and it involves every academic discipline, every government department, every form of business and every part of civil society, and a great awareness of that on the world of politics.”

His journey—from a childhood spent exploring the outdoors to navigating dense urban environments—has shaped a career committed to integrating nature, culture, and people into the fabric of our built world. Believing that this focus is essential to creating resilient and regenerative cities, he continues to advocate for biophilic design and cultural wisdom as guiding forces in urban futures.

Honouring a Visionary: The Biophilic Blueprint and Newman’s ongoing legacy

The Biophilic Blueprint honours Newman’s ongoing legacy, carrying forward his vision of cities where nature, culture and people are seamlessly intertwined. By showcasing his work and insights, the publication amplifies the principles of biophilic and regenerative urbanism, inspiring readers, developers and policymakers alike to reimagine urban spaces that are not just sustainable, but alive with meaning and connection. In doing so, it continues Newman’s mission—turning curiosity and respect for the natural world into practical, transformative action for our cities.