The “Doctor” of City-Making: Ludo Campbell-Reid on Regenerating Urban Design

Published by The Biophilic Blueprint | Written by Anjelica Smilovitis, Founder

Ludo Campbell-Reid at Committee for Perth 2050 Summit. Photo: LudioXMedia.

A global urban planner is showing just how transformative a city can become when people—not cars or metrics—sit at the centre of its design.

Visionary urban planning leader Ludo Campbell-Reid sees cities not as machines but as living, breathing entities—capable of thriving or slipping into ill health depending on the choices that shape them. His work brings the focus back to people, a principle that feels obvious yet remains absent from many urban environments.

Our interview with Dr Fiona Gray highlighted how recent research shows urban spaces frequently fail to support human health—and, in some cases, actively contribute to harm (Makaremi et al., 2025; Valentine, 2024).

Cities built around metrics or motor-vehicle logic risk becoming disconnected from the very conditions people need to thrive. When nature is absent from the urban fabric, when cultural value is overlooked, and when community is not nurtured, a city loses its vitality.

Ludo argues that this disconnect triggers a ripple effect—weakening social cohesion and eroding economic value.

“The future of the planet is going to be determined by the way we plan, design, build and critically govern cities. The governance—the mayors, the councillors, the city establishments that run cities—have got to get better at this,” he explains.

Ludo is a global urban design leader, city strategist and keynote speaker with 30 years of experience shaping transformational projects around the world. As Director of Ludo Campbell-Reid Cities, he advises mayors, ministers, councils and city leaders on unlocking liveability, productivity and identity through bold, design-led strategies. He has contributed to major city plans in London, Cape Town, Auckland, and Melbourne, where he is currently based.

For Ludo, city planning goes far beyond roads and infrastructure—it is people-first, purpose-driven and grounded in values that function much like an ecosystem.

Committee for Perth 2050 Summit. Photo: LudioXMedia.

“Cities are humanity's greatest invention,” Ludo says. “They’re humanity's greatest challenge as well, and they shape how we live and how we connect. I don't see cities as machines.”

From this perspective, he approaches city design like a doctor—diagnosing a city’s ailments and restoring its vitality through holistic action. He also likens cities to companies, encouraging a mindset that genuinely cares for their “customers”—the people who inhabit them.

This mindset contrasts sharply with sprawling, cookie-cutter developments that prioritise construction over community and long-term vitality.

Ludo tells The Biophilic Blueprint when cities are treated like machines, they lose touch with their customer’s needs—and can create disenchanted places without purpose.

Only when city-makers focus on human needs—much like a customer-driven organisation—can they generate solutions that revive a city’s pulse and create healthy change for current and future generations.

While metrics like Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and traffic flow are essential tools, he emphasises they only capture part of the story.

“I see cities as human—as living, breathing organisms that think, feel, and behave much like humans do. They can be confident. They can be anxious. They can be energetic. They can be tired. Cities can be connected, and they can be lonely places. Every city has potential. They go through cycles. Those are all very human traits.”

He elaborates on the metaphor: “The city centres are the brain and the hearts. Open spaces are the lungs of a city. That’s how the city breathes. The greenery—the alveoli of the lungs—the bushes, the trees, the plants. The streets and transport networks are the veins and arteries—and the people are the blood. It’s kind of an emotional thing.”

“I diagnose what I think are problems with cities. I look at cities and try to understand them in human terms. I try to understand their pulse, their emotions and their resilience. And then you put together plans to address those things.”

And for Ludo, this is not theoretical work. He pairs vision with action, collaborating with people committed to achieving meaningful transformation—something he sees as essential in any city that hopes to change.

In this feature, we explore Tāmaki Makaurau / Auckland’s transformation with Ludo’s guidance—a city once dull and grey, now a thriving hub of change. We highlight five key elements of a healthier city and examine global examples of transformative urban design.

Ludo Campbell-Reid in Melbourne.

Cities for Humans: Planning with People in Mind

When The Biophilic Blueprint first reached out to speak with Ludo, his first response was to compliment the language around city-making. “I really like the way you’ve used the word ‘radiant’ around changes in Paris,” he said. That simple comment opened a broader conversation about how language and concepts—such as viewing a city as a living human body or a company—can shift the way we think about urban planning.

At the time we spoke, Ludo was preparing to travel to Western Australia to deliver a keynote at the Committee for Perth 2050 Summit—a fitting setting for a city now confronting the very questions he raises: How do we design for people, not cars? And for a city like Perth, how do we restore vitality to an urban body shaped by sprawl?

By 2050, an estimated 70 percent of the world’s population will live in cities. Urban areas already consume roughly 80 percent of the world’s energy and generate about 75 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. This rapid growth underscores the urgent need for sustainable, people-centred planning that mitigates environmental impact while fostering liveable, resilient communities.

A crucial part of diagnosing a city, Ludo says, is understanding its “customer”—the people who live and work there.

“It’s important we ask the customers of the city what they want, and you start to respond and build up a strategy,” he says.

“Cities are almost the biggest company of all, if you think about the billions of dollars wrapped up in them, collectively and individually. So, it’s important that we get this right. That goes back to my attempts at being a doctor—let’s do this properly.”

Understanding human psychology is also central to his philosophy. “Anybody who is an urban designer, a planner, or an architect should have an undergraduate degree in psychology, because so often we don’t know what the customer wants.”

“Asking the right questions is about understanding the customer and building the city to respond to them,” Ludo explains. He cites behavioural experiments like the Piano Stairs in Amsterdam and literature such as Happy City by Charles Montgomery, demonstrating how thoughtful design can influence happiness, health and motivation.

Ludo Campbell-Reid embraces the four components of Ikigai.

Cities as Ikigai for Ludo: the “why”?

Ludo’s passion for dynamic, thriving cities is both professional and deeply personal.

Guided by Ikigai—the Japanese philosophy grounded in four principles that help people understand their ‘reason to live’—he approaches urban design with the same sense of purpose, meaning and alignment that Ikigai brings to individual life.

“I've spent my life …. and 30 years of my professional career … thinking about my ‘why’. For me it’s the intersection of those four things: do what you love, do what the world needs, do what you're good at and get paid for it.

“Cities are my Ikigai,” Ludo tells The Biophilic Blueprint. “They're my passion. They've been my purpose for many years. They've been my profession, and they've been my livelihood.”

He describes his career as a blend of design, leadership and transformation backed by action. “It’s not just talking about things or leading the conversation or thought-leadership but actually doing things. It's being at that forefront of that work—in London, Cape Town, Auckland, and more recently, in Melbourne—where I've had that direct lived experience.”

Auckland Art Gallery. Photo: Ludo Campbell-Reid.

New Zealand: Tāmaki Makaurau / Auckland as a Case Study

Ludo’s career has taken him around the world—and we delve into Tāmaki Makaurau / Auckland as an example of what is possible. He was appointed as Auckland and New Zealand's first ever Design Champion and General Manager of Auckland Council’s Auckland Design Office (ADO), in 2005 and started in 2006.

Leading a team of 54 multi-disciplinary design professionals—urban design, architecture, landscape architecture, universal design and place activation—he spearheaded Auckland’s people centred design-led urban transformation.

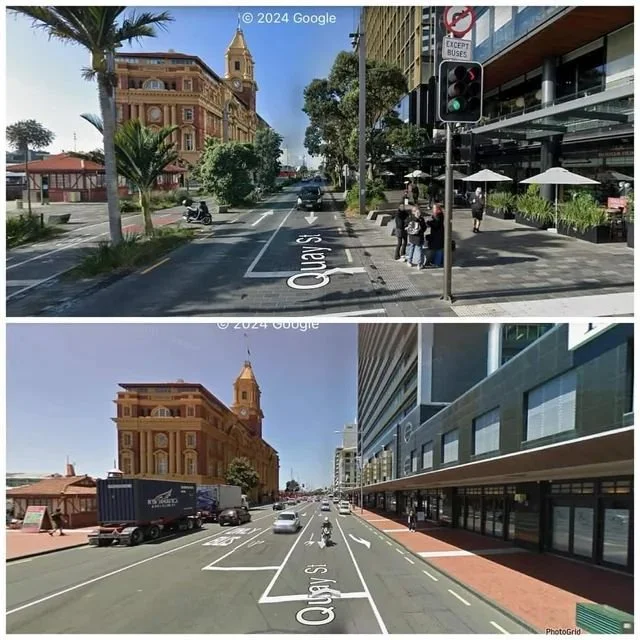

“I found a dull grey boring city that had lost its way. A city in the 1950s with the highest passenger transport patch in the entire world, per capita, and by 2005 had the highest ownership of cars per capita in the whole world. Auckland had taken a certain path and decided that trams were not good, and ferries were not something to move people around in.”

That mentality has now shifted.

Over the past two decades, Auckland has evolved from a car-dominated landscape into a vibrant, breathing urban ecosystem—where culture, nature and design intersect, and people sit at the heart of it all.

His deep involvement in the work entailed projects such as the multi-awarded Wynyard Quarter Waterfront regeneration, the City Centre Streetscapes and Shared Spaces programme, the Auckland Art Gallery redevelopment (winner of the 2013 World Building of the Year at the World Architecture Festival).

It also included the Auckland Design Manual, the award-winning City Centre Master Plan 2012 and the Lightpath, a “hot pink” soaring cycling super highway on a formerly disused motorway off-ramp.

Centring Pacific and Māori Culture: The Role of the Te Aranga Principles

One of the highlights of Ludo’s work in Tāmaki Makaurau / Auckland, in alignment with The Biophilic Blueprint, is the Te Aranga Principles—shaped over many years in partnership with Mana Whenua, and applied across major public and private developments.

Ludo emphasises that a key part of his work in Auckland has been—and continues to be—reflecting culture back into the city.

“I was approached by Mana Whenua .. the traditional owners of the land. They are from Auckland … people of the place. They said they didn’t see themselves in the city. They didn’t see their faces in the places. So, we introduced this idea of the Te Aranga Principles,” Ludo explains.

The principles offer a framework for strengthening Tāmaki Makaurau’s sense of place, helping everyone who lives there connect more deeply to the land and its cultural foundations. The principles guide practitioners in working respectfully and effectively with iwi/hapū, ensuring projects enhance both the natural landscape and the built environment while centring Mana Whenua values at every stage.

“That was an important values based reviewing tool to use against projects that are both public and private.

“In time you will start to see a more Pacific and Māori looking city. It won’t happen overnight, because it can’t be changed overnight. It’s from art works right through to installing mussel beds in central cities on the waterfront, to start to clean the harbour,” he said.

The Te Aranga Principles guide the creation of spaces that nurture wellbeing, foster connection and strengthen belonging—closely aligning with biophilic design by grounding places in nature, culture and community.

Ludo Campbell-Reid.

Five Keys to a Healthier City

The Biophilic Blueprint requested Ludo share five key elements of a healthier city—acknowledging the list goes far beyond what we have included in this feature.

People-centred cities

“Cities have got to be designed around people, not transport systems. Obviously, the transport system is the enabler of people to move and access things they want to do. But I design the city for people, not cars. At the epicentre of all of this is humans—the customer—and I don't see the customer very often at the centre of projects, particularly in infrastructure projects or city projects. It's not a vehicle or a bus or a train or an airplane or whatever. It's about the human.”

Nature as Infrastructure

Ludo emphasises the importance of prioritising nature in the built environment: “If the river's healthy, the city is healthy. It’s a great litmus test. The other great litmus test of cities is children. If your children are happy and comfortable and feel safe, then you've done a pretty good job.”

Nature as infrastructure lies at the heart of biophilic design. It spans restorative and regenerative approaches—both inside and outside buildings—and global examples show its power when cities peel back layers of hard infrastructure to restore the natural systems beneath.

He points to Singapore’s “incredible” green and blue systems, where water and flood management are integrated into a broader ecological framework. Seoul offers another example of transformative urban thinking: the Cheonggye Stream, once buried beneath an elevated highway after the Korean War, was uncovered in a 2005 restoration that removed the freeway and revived the waterway. Today it is a vibrant public space, complete with walking paths, art, and restored habitats—a dramatic urban renewal Ludo likens to “open-heart surgery… like a full bypass.”

Ludo also highlights the concept of a “sponge city,” an urban planning model that leverages green infrastructure to absorb, retain, and reuse rainwater, managing floods and droughts while improving water quality. He describes it as a city that “absorbs, expands, contracts, and is alive, not dead.” First initiated in China in 2014, the sponge city concept tackles urban water challenges including surface flooding.

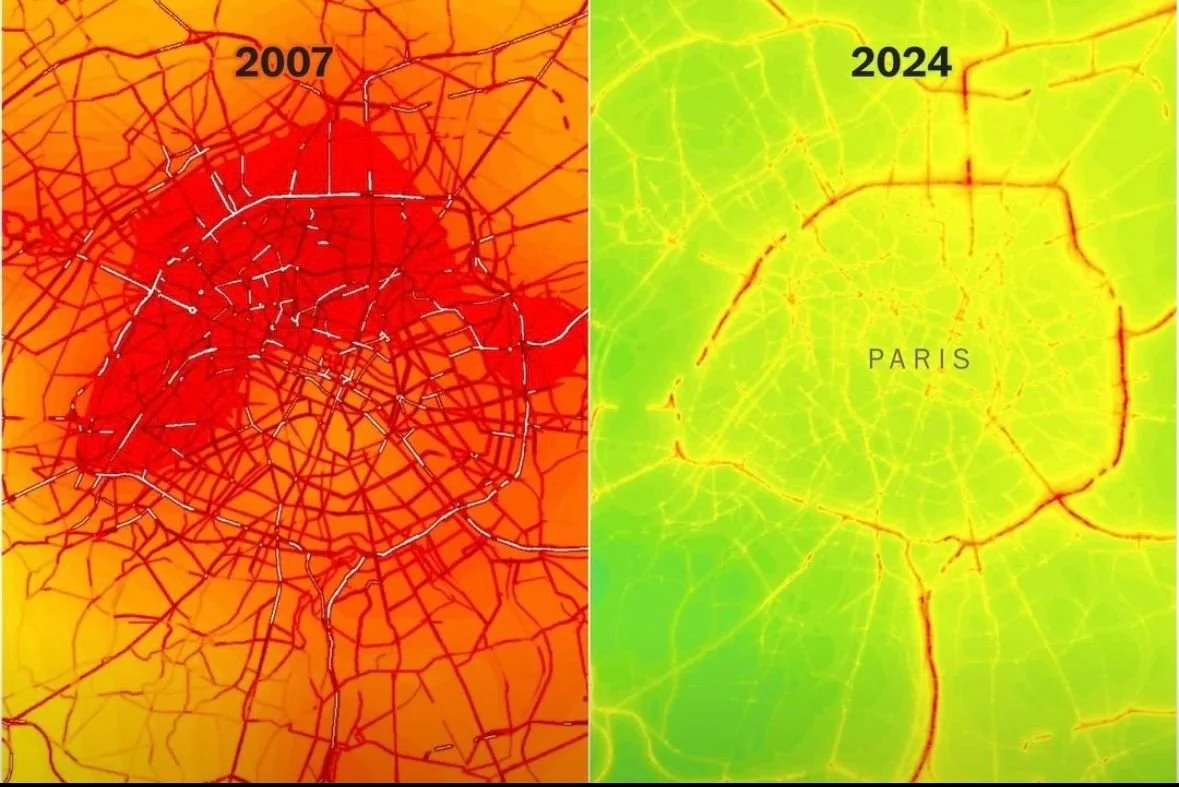

Paris’ air pollution dropped dramatically as the city limited car traffic and expanded parks and bike lanes.

Long-Term Thinking and Leadership

Ludo said at the core of healthy city planning is long term thinking—and the understanding that if it’s taken years to get to a certain point, it will take time to unravel. His optimism is backed by countless stories of change around the globe, with one standout being Paris.

In 2007, Paris was suffocating under red-zone levels of NO₂ and particulate pollution. Seventeen years later, by 2024, those hotspots have been reduced to a narrow band along a few major roads—the result of deliberate, sustained political leadership and a citywide shift toward cleaner streets.

”It’s about leadership from the top,” Ludo says crediting Anne Hidalgo and her team in Paris.

A Washington Post investigation shows that over the past two decades, Paris has dramatically reduced car traffic by replacing road space with bike lanes, expanding green areas, and removing more than 50,000 parking bays.

Heat-map records reveal a transformation from a city once glowing in “pulsing red” NO₂ concentrations to one where elevated levels are now largely restricted to major road corridors. Together, these shifts demonstrate how bold, long-term policy can reshape public health.

Ludo emphasises that Paris’s transformation—and that of any city achieving remarkable change—is the result of deliberate, sustained action.

Under the visionary leadership of Mayor Anne Hidalgo, the city restricted traffic in key areas, expanded separated cycling networks, planted thousands of trees, removed tens of thousands of on-street parking spaces, and accelerated the transition to cleaner vehicle fleets. These coordinated measures not only reshaped the city’s infrastructure but also redefined how Parisians experience public space, prioritising people over cars and demonstrating the tangible impact of committed, long-term urban leadership.

Walkability and Cycling as a Transit System

“Cities really thrive when they're more walkable. Cities, as in humans, thrive when they walk a lot more, when they bike, when they use public transport. Places like the Netherlands and Copenhagen … they've created demand for cycling by building separated cycleways. There are no helmet laws there, and they allow people to cycle, but they're all connected, and so you get on a bike and you can go from one place to the next without having to jump off your bike. That's why cycling is so sensational there.”

He adds a cautionary note: “If the majority of the city's budget goes on building motorways, well, you're going to get more people driving. You're never going to solve congestion by building more roads.”

Ludo explains that to truly enhance cycling and walkability, a city must create networks that make sense—paths should connect key destinations, serve a clear purpose, and integrate seamlessly into daily routines so that people naturally choose them over cars.

It’s not enough to simply create infrastructure; the routes must feel safe, convenient and enjoyable, encouraging regular use. Equally important is a mindset shift: cities can foster a culture of walking and cycling through initiatives like car-free days, public awareness campaigns, improved signage, attractive streetscapes and programs that incentivise active transport.

By combining thoughtful, purposeful design with strategies that make people feel empowered and valued as active users of the city, municipalities can cultivate streets that are both vibrant and sustainable.

Equity and Belonging

For Ludo, designing cities is fundamentally about fostering belonging and equity—ensuring that everyone who inhabits urban spaces feels connected, valued and included. He emphasises Australia as an example with a unique opportunity to care for both its natural and urban environments, highlighting that attention to cities is just as important as caring for the bush.

“Australians often romanticise the bush, but we’re one of the most urbanised nations on earth,” he adds from his base in Melbourne. While some see the city as profane compared with the profound countryside, Ludo argues that cities can—and should—be just as meaningful.

“The question is: what elements of Country—open space, nature and connection—can we bring into our central cities? Cities aren’t meant to be ugly and dangerous places with nothing going on, but rather a place which has great vitality.”

This understanding, he notes, can be applied across the globe, wherever cities seek to become more connected, vibrant and regenerative.

Aligning with The Biophilic Blueprint

Ludo’s approach to urban design embodies the very principles The Biophilic Blueprint champions. By treating cities as living systems, centring human experience, weaving nature into the urban fabric, and fostering equity, his work reflects a vision of cities where people and the environment thrive together. His focus on connectivity, walkability, ecological restoration, and cultural inclusivity captures the essence of biophilic design—creating places that are regenerative, restorative, and deeply attuned to the wellbeing of both people and the natural world. In documenting and celebrating these methods, The Biophilic Blueprint continues to highlight a future where urban life and nature coexist in balance and harmony.

Comment below: If you could ask Ludo one more question about the future of urban design, what would it be?

References and further reading

Airparif. (2021, October). Bilan qualité de l’air Île-de-France 2020 [Air quality report for Île-de-France 2020]. https://www.airparif.fr/sites/default/files/documents/2021-10/BilanQA_IDF_2020_UK.pdf

Ahmed, N., & Harlan, C. (2025, April 12). After Paris curbed cars, air‑pollution maps reveal a dramatic change. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/2025/04/12/air-pollution-paris-health-cars/

Auckland Council. (n.d.). Auckland design manual. http://www.aucklanddesignmanual.co.nz/

Carrasco, M. (2024, September 12). Re-Naturalization of Urban Waterways: The Case Study of Cheonggye Stream in Seoul, South Korea. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/1020945/re-naturalization-of-urban-waterways-the-case-study-of-cheonggye-stream-in-seoul-south-korea

Ville de Paris. (2025, June 25). Plan climat en 9E8O [Climate plan]. https://cdn.paris.fr/paris/2025/06/25/plan-climat-en-9E8O.pdf