The Talo Agroforestry Centre, Samoa: A Regenerative Vision of “Alive” Architecture

Published by The Biophilic Blueprint | Written by Anjelica Smilovitis

Tisha Lad, a recent graduate from Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand.

An architecture student has set out to explore what design can become when it truly listens to place. Her work weaves ancestral stories with regenerative thinking, responding to land, climate, disasters and community—creating a centre that feels deeply rooted, adaptable and alive to its context.

Tisha Lad is a recent graduate of Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand, where students are encouraged to approach design through the lens of regenerative architecture—a philosophy that prioritises ecological health, social equity and cultural continuity.

She was first drawn to study high-tech architecture intrigued by modern forms and building technologies. But as her studies progressed, Tisha shifted her purpose and passion toward creating architecture that restores ecosystems, supports communities and remains grounded in culture and place. Rather than treating architecture as a static object, her work reimagines buildings as living systems that integrate tradition with modern capabilities.

This means designing for place—taking into account climate, natural disasters, access to building materials and infrastructure and the needs of changing generations.

“Regenerative architecture, for me, is a way of healing both ecologies and communities. As a designer I want to keep designing projects that give back to the environment and community,” Tisha explains.

“Going into the future, we're noticing climate change getting worse, people are hating on construction and cities and the urban environment, and how it creates pollution,” she explains. “My thinking is about how can we design buildings that don’t create more pollution but instead resolves that—so designing more for the environment, nature and more for people. And restoring the relationship between land, people and culture, and designing something that's more unique to the site.”

“I've done that with my previous projects—to make it a unique piece that you can't just copy paste anywhere else.”

Her interest in regenerative, site-responsive design led her to create projects that integrate ecological systems, cultural narratives and community engagement—architecture that is alive, flexible and resilient.

The Biophilic Blueprint sat down with Tisha to explore her philosophy and a signature project that encapsulates her approach: the Talo Agroforestry Centre in Samoa.

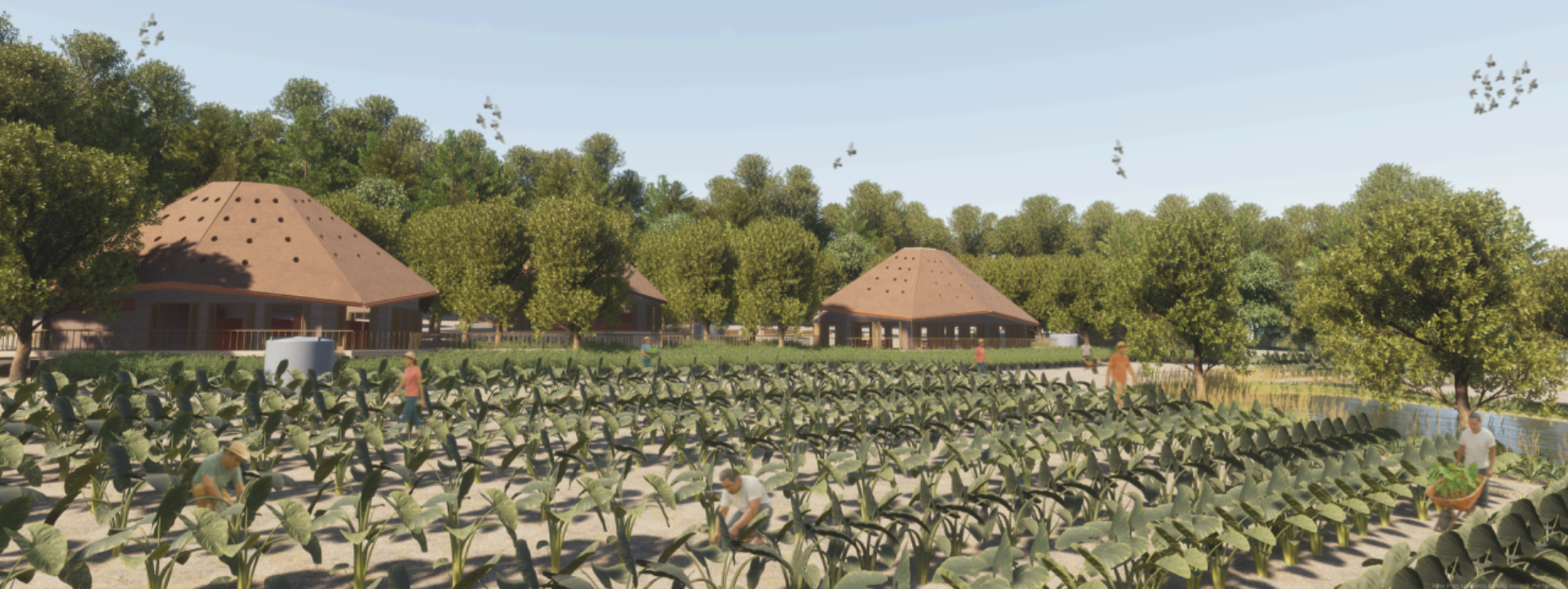

The Talo Agroforestry Centre rooted in tradition, growing for tomorrow. Photo courtesy of Tisha Lad.

The Talo Agroforestry Centre in Samoa

One of Tisha’s most compelling university prototype projects is the Talo Agroforestry Centre, a conceptual design located on Savai’i, one of Samoa’s main islands, in the Palauli District. The centre exemplifies her design philosophy: it responds not just to human needs but to cultural and ecological systems, integrating agroforestry, water management and ceremonial spaces.

The project weaves together ancestral stories with regenerative thinking, while responding to the realities of place—including natural disasters—to create a design that feels deeply rooted, adaptable and specific to its context.

The project’s three constructed wetlands, surrounding streams and layout all support ecological function while embedding cultural significance. Tisha incorporated agroforestry and ceremonial pavilions, reflecting sacred stories and practical daily use.

“The Talo Agroforestry Centre is about ecology, people and culture. The project is inspired from the myth of the taro (talo). The myth was how taro came from the gods and nourished the people of Samoa, and how over generations, that one Taro made different forms,” she says. “The aim was to connect the story, ecology and architecture into one project.”

The design also responds to place—recognising that architecture must be shaped holistically by the needs of the land, the people and the generations who will live with it.

Take Savai’i, for example. The island is no stranger to natural disasters. Over the years it has been struck by multiple cyclones — including Val (1991), Ofa (1990) and Evan (2012)—wiping out traditional homes and devastating crops.

Tisha shared with The Biophilic Blueprint that her research revealed how the fale—Samoa’s traditional thatched dwelling—had been severely damaged by a cyclone, and with the knowledge to rebuild these structures rapidly disappearing, she saw a need for design that could help preserve both the architecture and the skills to maintain it.

“It destroyed it to the point where they couldn't find anyone to fix the thatching roofs, because nobody remembered or knew how to rebuild a fale. Even if they did, they were too expensive to hire. That was one issue I came up with. I wanted to design an architecture that reflects the traditional fale architecture from Samoa, but also in a way where if it's destroyed, the locals are able to repair it without having to spend too much money on it,” Tisha says.

The design incorporates off-site prefabrication, allowing buildings to be relocated or rebuilt easily if environmental hazards strike. “Because it is off-site manufacturing, you can easily be assemble it and then reassemble it somewhere else and relocate the whole project. That was one other aspect—and also having a simple design as well. If the he locals wanted to, they could easily replicate the whole building, because it was a simple design.”

Tisha Lad presents the Talo Agroforestry Centre in Samoa.

Rooted in Nature and Culture: Agroforestry and connection

Architecturally, the design is inspired by the Samoan fale with the pavilions adopting open-sided structures with raised floors and expansive roofs, encouraging natural ventilation while remaining adaptable to social needs.

At its core, the project is agroforestry-based, growing taro, yam, cassava, coconut, banana, and pineapple in intercropping systems. Constructed wetlands filter water naturally, creating a closed-loop water system independent of municipal supply.

The project also doubled up as an emergency shelter as well.

Tisha’s design philosophy emphasises community empowerment and resilience. The project includes workshops to teach locals and visitors how to cultivate crops and engage with ecological practices, as well as pavilions designed to accommodate traditional Samoan ceremonial practices.

The layout is intentional: the north end is tapu (sacred), housing ceremonial halls and seed banks, while the south end is noa (everyday), hosting cooking workshops, market halls, and production facilities.

“At the top, I designed activities, ceremonial halls, seed banks, and further south, market halls, production house and cooking workshops,” she explains. “The left side, the roofs were more taller, so they were more connected to the gods. As you went down to the south, it was lower in height with the roofs. So, it was more grounded.”

Tisha also explained how this thinking shows up in the crops themselves. Short-term crops like taro, yam and cassava have shallower roots and are planted higher in the system. Below them, longer-living crops such as coconut, banana and pineapple are planted deeper, because they are more permanent and continue to support the landscape over time.

Agroforestry terraces with view toward main pavilion (seasonal cycles). Work by Tisha Lad.

Alive Architecture as a Regenerative Framework

Tisha shared her approach to regenerative architecture, grounded in the belief that buildings can be more than functional—they should respond to context, shaping how people engage with the land and with one another. For her, regenerative design means creating spaces that “adapt rather than resist change.”

“Architecture which is alive responds to more than function. It performs through context by speaking to place, drawing meaning from the land and shaping how people live together. Rather than architecture as a fixed object, it should be a regenerative framework that sustains ecology and culture while enabling resilience for generations to come,” Tisha explains.

This approach challenges the idea that architecture must be static or extractive. Instead, regenerative design shows how buildings can:

Restore ecological systems from wetlands to agroforestry landscapes.

Preserve and embed cultural practices, linking contemporary design to traditional knowledge.

Empower communities, enabling local maintenance, repair and stewardship.

Respond to climate risks such as cyclones and flooding through adaptable, resilient systems.

In doing so, architecture becomes a living framework—one that nurtures both people and ecosystems and evolves alongside them. Tisha explores these ideas further in her academic work in an Essay on Time, Culture, and Ecology in Practice/ The Talo Agroforestry Centre as Regenerative Architecture.pdf.

Central to her approach is the value of feedback. Open to critique, Tisha reflected on suggestions for her project—including refining the skylights and deepening the integration of the design’s narrative. She acknowledged that with limited time, every project leaves room for improvement. What stands out, however, is her mindset: she sees both biophilic and regenerative design as evolving practices, and believes designers must be willing to recognise limitations, learn from critique and continually refine their work.

Tisha Lad looks ahead with Australia on the horizon in her architecture career.

New Zealand to Australia: From Classroom Ideas to Real-World Impact

Having completed her Bachelor’s degree, Tisha now looks toward the next stage of her architectural journey in Australia, seeking both further study and professional experience.

“I’m hoping to pursue that in Melbourne. I’ll continue exploring how to do better. I think I’ve done a good job with this project, no doubt, but I could do a better job creating a design that’s simple yet more unique—while continuing to include community, ecology and culture in architecture.”

Her visits to Melbourne have revealed opportunities for regenerative architecture—but she also notes a lack of Indigenous cultural presence in the city’s built environment.

“I’ve been to Melbourne a couple of times now, and I’ve noticed that it’s mostly Victorian architecture. But Australians also have their own Indigenous culture—and I don’t really see that anywhere. If they embraced it a lot more, Australia would be so much more unique,” she says. “What I will bring to Australia would be very valuable. I think Australian architects really need to work on embracing the Indigenous culture.”

“I’d love to work with a firm that does this really well—and firms that work with local communities. I’m excited for that,” she says. Her goal is to refine her craft while embedding regenerative, culturally grounded principles in real-world architecture.

How Tisha Lad’s work aligns with The Biophilic Blueprint

Tisha Lad’s work exemplifies the principles at the heart of The Biophilic Blueprint: designing for connection, resilience and harmony with nature. Her approach to regenerative architecture goes beyond aesthetics or functionality—it embeds ecology, culture and community into the very fabric of her projects. The Talo Agroforestry Centre demonstrates how architecture can support local ecosystems, restore cultural traditions and foster social interaction, creating spaces where both people and nature thrive.

Comment below: If the next generation of architects embraces culture, ecology and community, how might our cities—and our lives—be transformed?

References and further reading:

List within essay by Tisha Lad.

Arch-Exist. (2025). Interior view of Driftwood Village Centre [Online image]. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/1033159/the-driftwood-village-center-primary-architects

Ayala, L. (2015, November 30). Exterior view of the Hilltop Arboretum pavilions [Online image]. InRegister. https://www.inregister.com/features/sharing-hilltop-arboretums-hidden-secrets

Alonso, C. P. (2021). Deep-time architecture: Building as material-event. Journal of Architectural Education, 75(1), 142–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.2021.1859906

Dupre, K., & Bischeri, C. (2020). The architecture of resilience in rural towns. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, 14(2), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-07-2019-0178

Fale Malae Trust. (n.d.). Project detail. https://www.falemalaetrust.org.nz/project-detail

Jasmax. (n.d.). Fale Malae proposal visualisation [Online image]. https://jasmax.com/projects/fale-malae

Lake|Flato. (n.d.). Louisiana State University Hilltop Arboretum. https://www.lakeflato.com/project/louisiana-state-university-hilltop-arboretum

Lelaulu, T. (2024). Maumoana: An indigenous design framework for regenerating Moananui living systems [Doctoral thesis, Auckland University of Technology]. Tuwhera. https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/items/f59903e5-db90-4f58-8707-338ae168ba7b

Malone, C. (2018, November 10). Exterior view of traditional Samoan fale [Online image]. Medium. https://medium.com/@cameronmalone/samoan-culture-d5f03b698a4e

Oktay, D. (2017). Lessons for future cities and architecture: Ecology, culture, sustainability. In Mediterranean Green Buildings & Renewable Energy. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-30746-6

Pallasmaa, J. (2017). Architecture and biophilic ethics: Human nature, culture, and beauty. In E. Führ (Ed.), Ethics in architecture: Festschrift for Karsten Harries, 22(36), 57–69. https://www.cloud-cuckoo.net/fileadmin/issues/en/issue_36/article_pallasma.pdf

Refiti, A. (2014). Mavae and Tofiga: Spatial exposition of the Samoan cosmogony and architecture [Doctoral thesis, Auckland University of Technology]. Tuwhera. https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/items/16292b4a-0858-491e-9c7b-f26c06a15202

Shuang, H. (2025, August 21). The Driftwood Village Center / Primary Architects. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/1033159/the-driftwood-village-center-primary-architects